By Heidi Rader, Professor of Extension at University of Alaska Fairbanks

Steve and Sara Masterman grow fruit near Fairbanks, Alaska. I had the pleasure of interviewing them about their decades-old orchard and was blown away by the depth of their knowledge of growing fruit in a cold climate. Steve described it as an addiction.

Steve grew up on a 12-acre farm in Wales, United Kingdom. His family raised cattle, chickens, turkeys, and ducks, and had a small orchard. He couldn’t believe it when he heard about a guy growing apples off Chena Hot Springs Road. He had to see it for himself and soon bought his first two apple trees from Clair Lammers.

It was 2007, and those were some of the last trees Clair sold. For many years, Clair was the master fruit grower in Interior Alaska and taught Steve how to graft.

In Alaska, a scion, or part of a tree that will fruit in our short growing season and that is also tasty, is joined with a very cold-hardy crabapple rootstock. Two trees quickly turned into 50 or 60 trees on a quarter-acre lot, which the Mastermans describe as their test orchard. They later acquired an additional lot (about 3 acres), which they cleared and planted over a period of about eight years. They used what they learned from their test orchard to plant their larger orchard. Still, Sarah laments they don’t have quite enough space for everything they want to do — which is a lot.

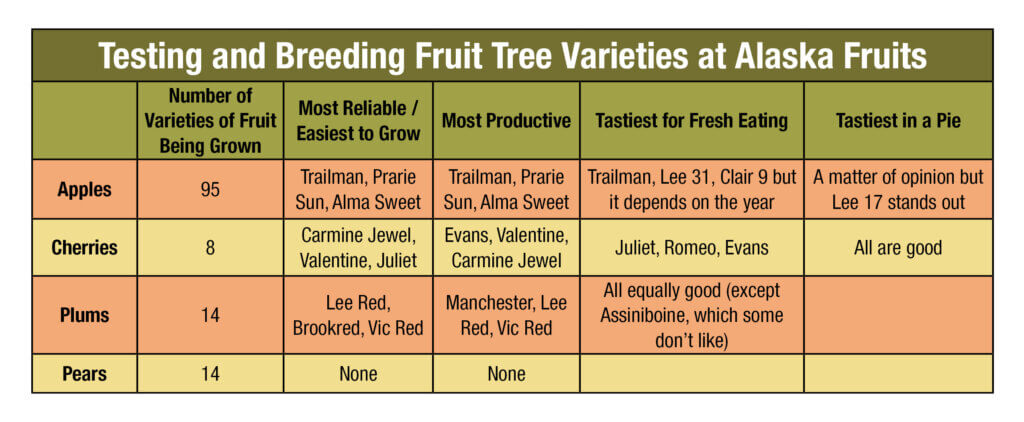

In addition to hosting a u-pick apples site, they sell trees in Alaska and to growers in other states with cold climates and short growing seasons. Over the years, they’ve tested more than 300 varieties of fruit (mostly apples but also cherries, plums and pears). Many of these were also tested or grown by Clair and developed by the University of Saskatchewan Fruit Program, which is one of the coldest sites for fruit and berry breeding in North America.

But it’s even colder in Interior Alaska. Now Steve and Sarah are breeding their own varieties and rootstock. They’re experimenting with grafting techniques, including timing, which is important in short growing seasons. They’ve learned how to care for the fruit trees in the winter and summer in Fairbanks.

“None of this is written down. A lot of it is by trial and error,” Steve said.

Sarah added, “There just is not a lot of research that has been done in this kind of climate.”

To be successful, they’ve had to develop their own manual, techniques, and varieties. They freely share what they’ve learned on their website, in workshops and on the farm.

Testing and breeding varieties

When it comes to breeding, first they ask if the plant will survive the winter. Then, will it fruit during the short growing season? Finally, does the fruit taste any good? Other questions may be whether the fruit is best fresh, good in a pie, or suitable for cider? Most of the apple varieties grown in Alaska will not store long, although there may be some that store for a couple of months. When looking at rootstock, they’re looking mostly at survivability, productivity and compatibility with different varieties.

Testing 300 varieties of fruit trees over the years takes a lot of time and space. They’ve come up with more efficient ways to test varieties. Instead of planting individual trees to test each variety, they now graft up to 30 different varieties on one tree so that what would have required 300 trees now only requires 10 trees. Further, they’ve found that some apple trees do fine when they are covered by the snow, but then once they get above the snowline, they suffer. The solution is to graft on more mature trees that are already above the snow line.

Here are some of the highlights of their research over the years:

For more information about the varieties they’ve tested, visit their website, www.alaskafruits.com.

This year, they’re looking forward to seeing cherries fruit and their trial apples make it through the winter. Last year, their Lubsk Queen fruited for the first time, and they’re excited to plant some of the new cherry varieties from the University of Saskatchewan. They’re also excited to grow their own rootstock and propagate more plants.

Want to plant a few fruit trees or an orchard?

Here are some of the basic steps to planting and maintaining a few fruit trees or an orchard in Alaska. You can find more detailed information in UAF Extension’s Growing Tree Fruits in Alaska as well as University of Minnesota Extension’s Growing apples in the home garden.

Step 1. Test and develop your soil. You’ll want well-drained soil with a pH between 6-6.5, high in organic matter with a depth of at least 18 inches.

Step 2. Decide on how you will protect your trees from moose and other would-be fruit tree eaters. Ideally, you will have a sturdy, 8-10 foot high fence to dissuade the moose with smaller gauge fencing to keep out rabbits, etc.. Use tree guards to protect the trees from small animals and other injuries from tools like weed whackers. You can also fence each tree individually although this can be hard to remember each year and hard to time.

Step 3. Choose the fruit and variety carefully and make sure you have a cold-hardy rootstock as well. The Mastermans have identified 50 apple varieties, six sour cherries (plus Nanking and Ping Cherries), six plum varieties, and five varieties of pears that are cold-hardy in Interior Alaska.

Step 4. Plant your trees at the recommended distance apart for the variety, which varies from 10 to 30 feet.

Step 5. Water, fertilize as needed with a little nitrogen, and weed regularly.

Step 6. Each year, prune your trees (see the links below for instructions) and thin the fruit. Additionally, the Mastermans have found that pruning above the level of snow helps keep branches from breaking when the snow starts to melt and settle in the spring. This is not a concern for cherries, which grow more in a bush format. Romeo cherries grow as a short bush and may benefit from being covered by snow to keep moose from finding them.

Step 7. In the winter, the Mastermans recommend brushing off the snow every time it snows and spreading coffee grounds to speed spring melt-off and add fertilizer.

Step 8. After three to five years you should be able to enjoy your fruit! Apple and cherry filling are some of the Mastermans’ favorite ways to use and preserve their fruit. Apple dumplings are one of my favorite ways to cook with apples.

Step 9. At some point, you may want to try purchasing rootstock and scion wood to graft your trees yourself.

Want to learn more? The Mastermans offer a wealth of information on their website and teach grafting and pruning workshops for the Folk School in Fairbanks. Fruit trees from the Mastermans can be purchased at the Fairbanks Soil and Water Conservation District Annual Tree and Shrub sale. The Mastermans have also had students from the AFFECT Farmer Training program visit their farm.

Questions about gardening or the Tribes Extension Program? Visit www.uaf.edu/ces/tribes Contact Heidi at hbrader@alaska.edu or (907) 474-6620. For more articles like this, go to: https://itgrowsinalaska.community.uaf.edu/

Heidi Rader is professor of Extension in partnership with TCC. This work is supported by the Federally Recognized Tribes Extension Program Project 2022-41580-37957. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

UA is an AA/EO employer and educational institution and prohibits illegal discrimination against any individual: www.alaska.edu/nondiscrimination.